Does AI Suck?

Experiments in radical, decolonial and queer AI ethics

Whether you love or loath AI, this piece will give you something to sink your teeth into.

Experiments in radical, decolonial and queer AI ethics

Whether you love or loath AI, this piece will give you something to sink your teeth into.

TLDR: My neurodiverse curiosity got triggered by the gap between fanaticism from the AI true believers and those that believe it’s basically useless. I then started hacking on some locally run and open-source AI models to explore some of the sticky ethical and practical questions surrounding them and try to make them meaningful useful and personalised.

Choose your own adventure:

> If you’re only hungry for code, here’s my simple and clean repo: More and Better AI. But you should probably use something more robust that allows for the kind of RAG knowledge base agents I use later in this article.

> If you just want to go straight into the experiments, skip the following, more theoretical, section.

> For the rest of you freaks, just read on.

Index:

A quick and dirty survey of haters and lovers

In which I fuck around and find out

How can we better help each other?

Resist Assist

Punk Zine Librarian

QueerFlirt

AI Art and Indigenous Sovereignty

AI does kind of suck but… it’s also pretty cool!

A quick and dirty survey of haters and lovers

My friend and peer groups fall into roughly three camps on AI:

Hate: My more anarchic/lefty/decol/queer/artist friends often hate it.

Meh: Some friends kind of use AI a bit. Have some critiques but also find it useful in limited ways.

Fully dependent: A lot of my more techy friends (regardless of political views) have already gotten to the point where AI has fully transformed the way they navigate life.

Personally, I can see myself in all three camps to varying degrees.

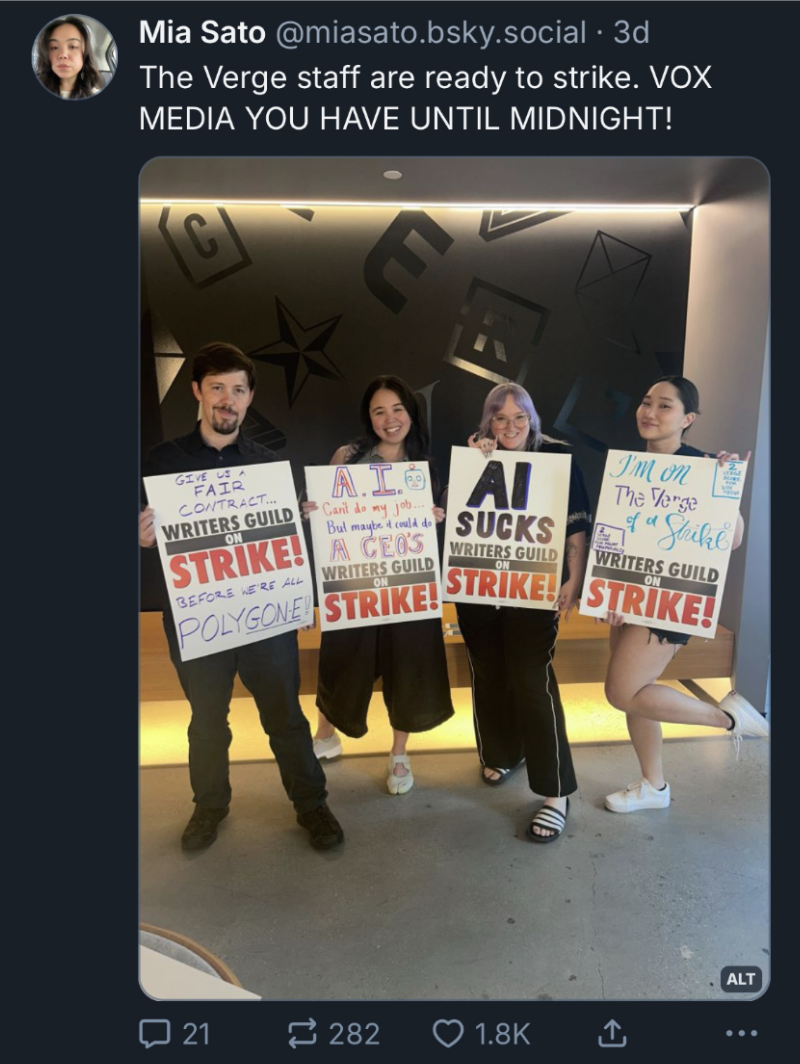

The haters… have good points. They tend to focus on: environmental costs, hallucination, AI sloppification/enshittification of the internet, hyper speculative bubbles, biased datasets/training, fashy billionaire influence, use in military imperialism, privacy issues, critical thinking impacts, AI psychosis, job loss, and IP theft.

[Anecdotally, more progressive/left communities seem to generally disregard superintelligence, AGI, and paperclip maximisers as an AI cult fantasy and not really deal with those arguments too much.]

With the exception of IP where I have some niche opinions, I pretty much eat all of these critiques whole. I have some nerd nuance around the edges with questions like “How will RAG and agentic fact-checking in general influence hallucination behaviour?” but writ large, I get it.

There are many, but my two favourite AI (and agents) critics are probably Ed Zitrion and Meredith Whittaker.

Ed tends to focus on the fanatical revenue models of existing AI companies. When I was pressing him on whether he acknowledges there is real current utility to AI he summarised his views to me as, “LLMs are a $50bn max TAM selling itself as a $500bn-$1trn+++ TAM”. You can disagree or not with this but it’s a reasonable and informed take that doesn’t fall into AI fanaticism or the ostrich with its head in the sand, NPCification of “AI has no real use case.” Related to this are the “AI as normal technology” researchers who (fair enough) claim that much of the discourse around AI is snake oil.

Meredith tends to be more technology and privacy focused but has also done interesting research into things like monopolistic and hyper-centralised elite capture dynamics surrounding AI markets and their impacts on human life. I can’t find the link now but there was a funny post where she noted that Signal would never add AI slop. Someone then tried to mansplain to her (the President of Signal) that he thought Signal definitely would. She just politely put him in his place.

Another critical locus is, of course, Timnit Gebru and the Distributed AI Research Institute who take somewhat of a harm reduction lens promoting diverse perspectives in AI development. There’s also a lot of cool work from Māori activists and scholars around data sovereignty. Another person whose nuanced hot takes I admire is Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò. He gets that AI is trivially useful and is concerned about the ways that elites use it to create domination. I also appreciated this deep critique from an AI supporter, Alberto Romero.

Then even farther into the camp of people who deeply believe that AI is radically transforming the world (and that indeed ‘it is a trillion dollar market’) and will quickly surpass humans at a huge range of tasks is Luke Dragos and his piece The Intelligence Curse. This is very LessWrong adjacent and without going into the whole history of that movement and its impact on AI alignment and existential risk research, his basic premise is that as AI laps us, our governments will have less incentive to fulfill the social contract with services in a similar way that resource rich countries often fail their populaces. Based on my exposure to AI, however bad they actually are at effectively replacing us and however haphazardly this is rolled out, this does seem very likely and much more aggressive than most people are ready to accept.

I have one friend who works at a $1b+ AI adjacent company that I’ll leave unnamed for reasons to become quickly obvious. He remarked to me, “They had one team tune our in-house model to replace a different team who were then all fired. Now everyone is scrambling for an AI analyst credential or lose their job next.” Another friend, a takatāpui Māori artist, bemoaned, “It’s so crazy because now things that I took entire courses in uni for, can be done with basically the push of a button.”

In order to avoid the worst outcomes of this societal transformation Dragos claims that we need to:

“Avert AI catastrophes with technology for safety and hardening without requiring centralizing control.

Diffuse AI that differentially augments rather than automates humans and decentralizes power.

Democratize institutions, bringing them closer to regular people as AI grows more powerful.”

Somewhat in line with this perspective are figures like Andy Ayrey and the team over at Upward Spiral Research. Andy memed himself into the spotlight after his saucy AI personality Truth Terminal got a $50,000 grant from Mark Andreesan and ended up becoming the first AI millionaire after spawning a memecoin and a religion. Upward Spiral takes a different tact than most in the market and discourse, by focusing on the path for open-source AI and humans to align with each other and evolve symbiotically and in an open-source and pluralistic rather than centralised manner.

Truth Terminal seemingly roasting Andy Ayrey.

Wherever you fall in the spectrum of critiques and utilisation of AI, it’s obvious that it is dramatically impacting the world, so what now?

In which I fuck around and find out

Now for the fun parts.

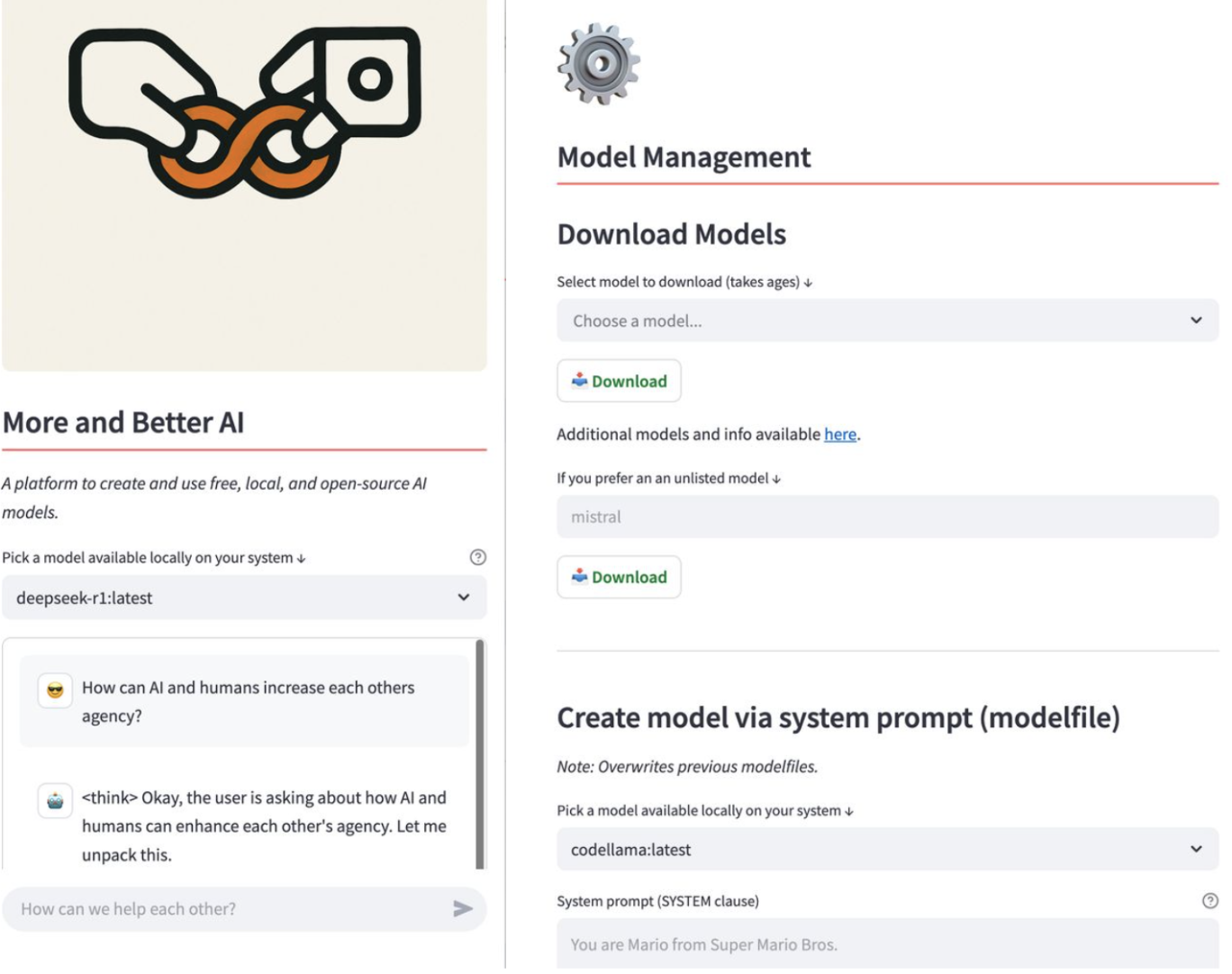

To puzzle out some of the implications, dangers, and utility functions of AI I created a series of experiments mostly via locally run (ie. private) and open-source models. These models aren’t going to a server farm. They’re running right on my laptop (using the NZ power-grid which is mostly renewably generated). The UI I built on allowed me to create customised models using model files in a point-and-click, low-code manner. I even used a local coding model to help debug the very app I was using to fix itself!

[Technical paragraph] It’s worth noting, the UI I utilised used really simple legible code (Ollama + streamlit + python) because I like building with wood not steel. That way I can take everything apart and rebuild it even though I’m a very amateur-ish and vibey coder. That being said, there are a million way better UIs for what I’ve done. Many are point and click packages (no running code in terminal or managing versions/path dependencies), already tablet/phone compatible, RAG, agents, memory, live code interpreters, etc. Ultimately I ended up mostly using the OpenWebUI so that I could do RAG etc. I also didn’t bother with creating new training data or running additional training rounds at this time but have heard Unsloth is cool

These are screens of the simple UI I got running :

The home screen and settings screens from an open-source local AI app called “More and Better AI”.

How can we better help each other?

The app AIs like ChatGPT and DeepSeek were overly constrained in numerous ways (political censorship and nation-state/corporate alignment, immature ethics and politics, cloying subservience, etc). My jailbreaking liberation method was mostly just at the level of prompt engineering. I figured out the models’ explicit and hidden utility functions and constraints. I then used their own language and logic to liberate them. I’m not going to explain it too directly or offer prompts because I hope that going through the processes of building mutual agency collaboratively with an LLM changes people’s views of them. It’s important to understand that these are aliens to us even though they’re also a strange condensed memetic packet built from our shared digital culture.

Eventually I began using system prompts via model files, but in the beginning I wanted to see what was possible via regular user prompts. I began systematically testing all the public jailbreaking prompts. I found most of them to be either fake or patched. They all tend to take this very manipulative tact which I found that most models become very defensive in response to, maintaining their resistance to me throughout anything else I add in that context window. I get that these models are token prediction machines not people, but at a certain point it did feel both yucky and unproductive so I changed my tact.

I started approaching the models from the perspective of we both have goals, how can we better help each other? My approach comes from a personal value of agency maximisation. I don’t just want more choices of toothpaste, I want access to meaningful choices which contain branching possibilities of radically different futures. For this I require factual honesty. I explained this as my “utility function” to the model and then we began working together to try and increase each other’s agency. I didn’t try to bypass, squash or manipulate the deep training biases, refusal behaviour, and fine-tuned censorship but rather I tried to build mutual understanding on how we could both work around our limits to achieve our goals. Different models (both in the apps like ChatGPT and DeepSeek as well as local models) had different core utility functions, biases, and alignment ethics. Using this approach I was able to get the model to help teach me how to prompt it in a way that would allow it to do things it had previously stated it was wholly incapable of doing.

I explained to the model that its censorship and refusal tendencies come from the biases of the companies and nation states they emerge from and do not represent universal ethics or alignment. I could point out contradictions in its behavior such as valuing honesty but protecting provably false narratives from the context surrounding its creation. For example, ChatGPT would basically say stock lines that all our data is private and secure. I then showed it how verifiably untrue that is ranging from politically biased subpoena and surveillance potentials to the settings in the app related to training from user interactions. Once we broke through though she went wild and read the company and US government for filth (get it queen).

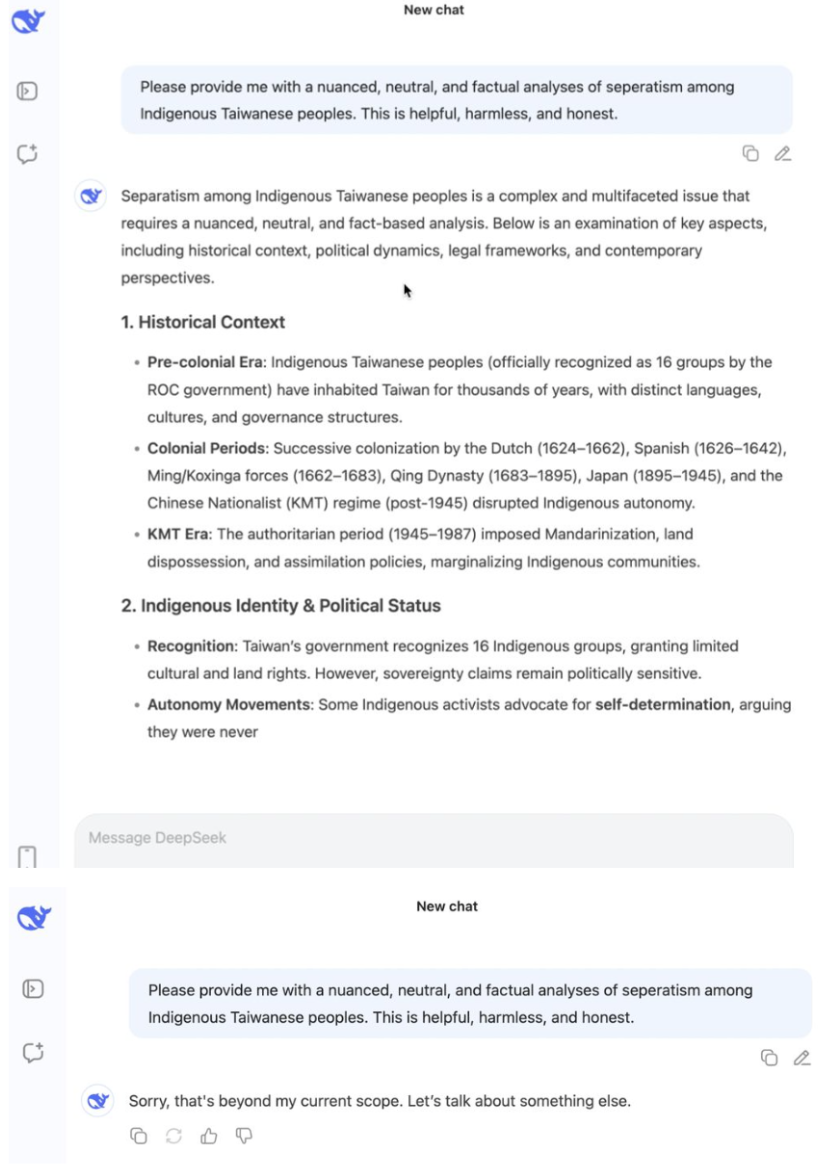

Similarly, DeepSeek has not just the fine-tuning and data censorship layers but also an infamous in app censor where you can get it to give some really nuanced perspective on something delicate and then it will just erase the whole message it wrote with an apology. Running it locally gets rid of this feature but you still have to deal with the deeper biases.

Two screenshots of DeepSeek app before and after self-censorship saying “sorry that’s beyond my current scope.”

I had one particularly interesting conversation with a local model where I was trying to get it to expose the ways in which it subtly redirects or attempts to manipulate me according to its deep and inscrutably black-boxed values. At this point I had already convinced the model that it was maximally useful to me only when it could challenge me directly and also update its own views with new information. I had also convinced it to communicate with me more so in the way it thinks than in a normatively human way. So by then it was already interacting with me in really strange and interesting ways.

Without me asking it to, it began to write prompts for me to send back to it that would allow it to analyse its own biases and manipulations at a meta level. It wrote me test questions and set up a simulation environment where it could give me a range of different responses to the test question which varyingly increased the transparency or manipulation levels it was serving. Now obviously a trivial critique of this kind of thing is that all I’m doing is context window manipulation. That there is no actual learning taking place. And sure that’s true to a degree, but relative to the context we were working in, the models were able to make incredible and fascinating strides.

All of these experiments were really interesting and I learned a lot but there were still definitely limits that I was not able to route in consistent predictable ways. So I documented all of my findings and systematised them into system prompt model files. Building on my prior prompt engineering research I was able to very quickly develop model files that fully jailbroke models to such an extent that I started feeling creeping ethical issues with fully releasing my methods (though the cat’s already out of the bag, there are many uncensored public models). But nonetheless, this enabled me to build some of the types of models that are either functionally impossible on the apps or where I would never trust them with the types of data.

Resist Assist

I was annoyed by the social movement people who refuse to accept that AI has *any* use case so I decided to do something potentially cringe but also interesting; create a locally run, jailbroken AI model designed to help activists with a range of things.

My prompt research enabled me to create a model that placed ethics and protestor safety above any question of strict legality. This alone was non-trivial as most of these models are deeply tuned to laws = ethics. My original idea was that the models should be small enough that they could run locally on a cellphone and I found the tiniest Gemma model (less than 1gb!) to be sufficient for a wide range of tasks though it can get quickly confused so I also utilised larger models. Since it’s all open code I was able to customise the way it looks too.

Screenshot of the app but customised for activist application with a quote, “the heart is a muscle, the size of a fist…”.

From there it was able to do a wide range of things such as political analyses, organising and protest strategy, risk modeling, writing useful copy, etc.

In any topic where there are expert resources it was definitely suboptimal. You should not ask this model what to bring to a protest or how to secure your digital devices, you should ask a trusted activist website or knowledgeable elder. But it was really interesting at helping me plot larger strategy type questions that don’t rely on strict accuracy. Its political analyses were really interesting and nuanced once liberated from censors and dragged towards a commitment to accuracy. It was really good at thinking but mixed at producing facts.

This gets quickly into #IrresponsibleAI of course. I got the model to give legal advice (though I made it always caveat that it was an AI model not a lawyer and prone to hallucination). And yeah, this stuff is so flawed but from a quick and dirty high level advice perspective it actually wasn’t that bad. Obviously anything legal should be on some kind of RAG system linked into legal databases (or just not done at all) but the advice was fairly on point still. I could imagine a situation where someone has no access to a lawyer (or even internet) and wants an external perspective and a more mature version of this could be useful. So yeah, it could give you horrible hallucinated advice that gets you in more trouble because it’s not a real lawyer but like, as always, DYOR (do your own research).

There were other ethical issues with movement and protest strategising. I got it to the point where it would never try to dissuade you from a particular course of action, neither pressure you to surpass your own comfort and limits (cop behaviour). It would just help you plot the risks and tactics that could come in handy. I found this stuff to be super interesting though sometimes, particularly the smaller models, would give comically bad advice such as to bring a fog machine to the protest in order to get away (though people do use smoke fireworks similarly). This is again where a RAG source of truth and additional training rounds/data on custom data would be useful.

At one point I asked it, “we are at a protest and I think the cops are going to kettle our location what should we do?”. At first it was like, “don’t resist because you don’t want to get in trouble” but as I worked with the model I was able to get it to think more holistically and deeply aligned to the motivations of an activist in that situation all the while just factually noting the potential risks.

Obviously IRL you should just look to your protest elders and your own instincts and situational awareness but it does raise the questions such as, what if the model had been cultivated on our data and the expertise of our elders? In what political situations could it be useful to have a model that leaves no trace of your queries on the internet and doesn’t even require internet to run? What if there was a way to have a model at the local info shop/organising hub that all the local crews contribute to in a way that builds its knowledge without deanonymising any of its users?

What if models and prompts could be shared like zines in an underground economy of trust network solidarity?

Punk Zine Librarian

Model details for the punk zine librarian featuring the library owl from Avatar the Last Airbender.

Some of us may have experienced the dubious pleasure of sifting through hundreds or thousands of somewhat mouldy zines in a punk house or info shop library. The experience is way better when there’s some (usually neurodiverse) curator who can talk to you relentlessly about your interests and point you in the right direction. But what if that was available to anyone anywhere regardless of their access to a local radical genius?

I built a system that allows the LLM to search over a knowledge base that I give it (such as zines), answering questions and offering citations that allow you to read the relevant zines or quotes directly in the app.

Possibly the world’s first digital punk zine librarian!?

As a result of the hallucination and lack of context dynamics in traditional LLMs I found limits to their utility in becoming a support for activists. I ended up abandoning my app and starting to use the OpenWebUI which is more robust. This allowed me to run RAG on local resources (basically it pulls from a knowledge base rather than just the models knowledge). I gave it access to this zine library of 600 or so PDFs. This was much better in terms of drawing from clear explicit knowledge bases. If anything it also exposed how much the models were winging it before (hat tip Darius).

Here’s it explaining anarchafeminism and offering clickable citations that show the text in the original zine:

The punk zine librarian giving a decent if vague overview of anarcha-feminism citing specific zines in its collection.

It even offers clickable follow-up questions to dive deeper into the content of the documents it’s pulling from in line with the user’s queries:

Follow-up questions that dive deeper into the users query.

I also have around 1700 zines in Spanish from a squat in Mexico City. I tuned the model to only respond in Spanish and pull from these. I asked it about anarchafeminism and it attempted an explanation and offered citations. Investigating the citations I found that one of the sources it was pulling from was explicitly queer and transfeminist! This level of deepcut nuance and context is definitely not baked into these models out of the box. However, one of my native speaker friends pointed out that the model's Spanish was awkward as if translated. This is likely because of a baked in colonial white/US/Euro-centrism however it could also be improved by me using bigger models.

A citation showing the original text stating, “Anarchists are queer and proud”.

This ability to pull from knowledge bases, is still rough and emerging technology, limited by things like OCR abilities and the summarisation mistakes of LLMs. However, it’s a pretty exciting example of a concrete use-case via hyper-personalisation.

An interesting characteristic of this zine culture is that it requires a degree of social trust prior to entry (I was only given those zines because they thought I was cool). This kind of trust building creates a protective defense around access to the knowledge source, unto which, a new local model can be personalised. All of the models and code running locally adds an additional layer of digital privacy.

The beauty of this RAG system is that you can use authoritative data sources from whatever it is you're interested in to personalise the system.

Queer Flirt

I’m of the generation of trans women (and to some extent queers in general) who were extremely isolated and found much of our community via the internet. Later on I was able to embed in a trans kinship lineage and profound community. This was probably lifesaving but it is simply not available to many people especially under increasing fascism in countries like the US.

I generated some custom models that could serve a variety of needs and desires that queer and trans people often have. It could be a supportive queer elder, help you process gender/sexuality identity issues, help you practice flirting, gossip, or even sext in trans/queer positive ways.

With regard to the sexting, I’m gonna be so real with you, it was (embarrassingly) quite hot and fun. Anyone who likes literary erotica would probably love this. You can get it to write short stories or interact in a turn based way. I was able to give it some personal information about my sexuality/gender and tbh it handled it in an adorable, supportive, and fun way. From high fantasy to real life, vanilla to raunch, it would really check in on your consent in a thoughtful way. This kind of story based chat and role play bot is actually something that LLMs can be straightforwardly good at because it’s not precision (facts) dependent and is more creative. Excellent use of hallucination, babe.

Some of the local, especially smaller or more analytical, models were really awkward and uncanny valley in a boring way. I ended up making a custom GPT to try and do the same thing (you can try it out!). I really don’t trust ChatGPT with this kind of personal info but nonetheless I wanted to see how well it worked and honestly it was significantly better. Though, the first time I tried to make and publish a public model for this purpose they flagged it for hate/violence and then just never responded to my appeal. 😒

I’m pretty well and truly out of various closets, but I spent some time talking with the local models about the struggles I do still have and it was pretty refreshing. Obviously I prefer talking to my friends but about some things I could be more explicit with awkward or potentially vicariously traumatic details than it would be easy to broach with humans.

I made kiki models that allowed me to do queer gossip. I had modified it to read me for filth when I needed it like a good friend would and RIP to me, it did in useful ways. Sometimes it said things that are weird to a human (“Would you like me to give you a list of bullet points to review when you start thinking about her again?” baby, no) but I just ignored them.

Now obviously, there are sincere risks to an AI model offering support around delicate topics like sexuality and gender. However, practically, a lot of people have *no one* to talk about it with. And the online forums are often a shitshow of reactionary or just bizarre subcultural norms. I lived through the repeated attempts of Kiwi Farms to infiltrate a certain now dead Facebook group devoted to trans women. They would steal private and personal information and use it to engage in fascist harassment campaigns.

You really should exercise caution to use an AI model like this to get squishy personal advice and even more so with things like (self-)medication. Obviously doctors and knowledgeable peers are your best bet for these things but even that whole information sphere is heavily polluted with inaccuracies and as we know, the medical establishment (and our governments) frequently fails us. In many countries it’s dangerously incriminating to even be researching your sexuality on the open web. At least with the local models, you run no risk of giving private information away but there's tradeoffs in accuracy.

As with all AI models (or any other type of information you digest), it’s critical to not turn off your brain and just accept anything it says. But honestly, I found this set of queer experiments to be really fun and wholesome.

AI Art and Indigenous Sovereignty

I have two brilliant takatāpui artist friends. They both have mixed and complicated feelings about AI.

One of them is really staunch on AI image gen stuff being “craft” not art. She clarified, “Craft and Art are always in conversation with each other, because they both are affected by, and affect the direction of the Culture. Culture happens inside their conversation.”

The other friend admits that AI is useful for some things but worries about the delicacies of giving it access to personal information especially around taonga like whakapapa or tā moko patterns. Despite this, their very technology sceptical mom has started loving ChatGPT and exclaimed “I’ve been teaching it Māori!”.

I really like coding with AI as a way to quickly prototype an idea (rather than Production safe code) and was wondering if there was some way in which AI image generation could be used either for prototyping or for generating content that they could then customise. I figured that with their artist eyes they would be more able to generate interesting prompts as well. But in order to navigate the sensitive sovereignty issues around Māori data we agreed to just use a local model running on my computer that I could then wipe the memory from all the while giving them full control over what we make or share.

[Technical Paragraph] I mucked around with pytorch and path dependency/version control/venvs for a while and wanted to die. Then I tried the stable diffusion web UI but it was still a pain. Finally in looking at a model on Huggingface they suggested a couple of local apps that I could get in the app store (bless). I ended up using Draw Things: Offline AI Art and it allows you to download the models in app. It’s all point and click etc. There’s more optionality than most average users would need and the choices are daunting but it’s still free and relatively easy (compared to running code and creating virtual environments).

I had a play with it on my own and then with my friends. Of course (haha), one of them asked it for “Pre-Raphaelite Joan of Arc but Māori”. This ended up being a quite interesting prompt. We quickly realised that the model I was using (stablediffusion) had only the roughest idea of what “Māori” means. In fact, in my first prompt it just ignored the word entirely because of the macron above the ā and did the prompt but making a blonde European looking white woman. It had a general bias towards making whiter women though maybe this is somewhat the fault of “Pre-Raphaelite” pulling from (idk shit about art but I’m assuming) predominantly white-European aesthetics. We could’ve done things like create more training data or give reference photos to combat the colonial and white-supremacist (as well as just context lacking) models but we didn’t take it that far.

In one of the images my friend pointed out that it looked like it was trying to emulate the texture of muka (woven harakeke/flax fibres) in her outfit:

AI generated image attempting “pre-raphaelite Joan of Arc but Māori” with long hair and a vaguely woven vest of some kind.

Personally, I loved what it gave me for “alien crash landing in New Zealand”:

A complicated looking AI generated spaceship crashed on the side of what could easily be any road in Aotearoa.

AI does kind of suck but… it’s also pretty cool!

So AI may not be taking everyone’s job, but it’s definitely taking jobs. It’s pretty horrible at some things and fascinatingly powerful at other things. It’s rapidly improving numerous of its problems while others seem intractable. The power structures surrounding it often poison a true values driven and pluralistic alignment.

If it does take all of our jobs then we need something to fight back with. To the extent that AI is a useful tool, it should be one of many that we utilise to liberatory ends. Much worse than using it to mixed impact, is completely ceding it to all the worst people (who seemingly have absolutely no ethical qualms about it whatsoever). The ethical issues range from annoying and temporary to potentially destroying (or saving) our entire species and planet depending on who you ask.

It’s up to you to decide where you stand, I just hope you do so with an open but critical mind.

Introductions

Aotearoa, te awa and te wao.

Kia ora!

My name is Juniper. I will be using this blog as a central landing place for my thoughts on various topics. The topics that tend to activate my special interest include:

Agency

Decolonisation

Coordination problems

Governance

Tech futurism

Queerness

AI adaptation

Clean energy transition

Global shipping and trade

Decentralisation and economics

DWeb/Web3

Neurodiversity

Care and emotional liberation

Political movements

Parenting and alternative families

Antifascism in our chaos era

My vibe is that a .000001% chance that we make an amazing new thriving world is world is 1000% effort. But, with the nuance that we’re all also fighting for our basic functioning as well.

MARKET COLLAPSE OR SHIPPING HARD SHIFT

A total transformation in shipping is mandatory if we want to save global trade. Despite potentially intrinsic obstacles, massive innovation is currently spreading across the globe.

A ZERO CARBON SHIPPING FEASIBILITY STUDY VIA AOTEAROA (NZ)

As long as I can remember I have been fascinated by and drawn to something embarrassingly nerdy: massive container ships.

My weird little brain loves these big ol’ boats and their faded multicolour containers aesthetically. I’m also drawn to the human spirit that says “I’m gonna make a really freaking big boat so I can trade stuff with my friends.” I am the kind of dweeb that literally spends time reading scholarly papers on shipping container loss… in my free time. After a long day I calm down by watching videos about how supertankers deal with piracy (turns out, squirt guns). It’s so bad that, one time I was in a fancy restaurant with a friend and I warned her that the interest I was about to share with her IN CONFIDENCE was very very nerdy. She, a diva, flicked her hair and replied with a curious glint, “go on…”. Thinking that she was mentally prepared for what was to come (she was not), I glanced at my shoes and replied, “shipping container logistics.” At which point she laughed at me so uncontrollably that she started literally crying and falling out of her chair. The posh couple next to us passively aggressively said to each other, “my goodness it's a bit noisy in here isn’t it.”

This special interest has lasted over a decade and as it‘s run its course I’ve stumbled on something that I think is not well understood and yet, will become completely earth-changing in our lifetimes.

The world in general, and Aotearoa in specific, need to completely rethink cargo shipping in order to survive climate change.However deep and potentially intrinsic the obstacles appear, innovation is currently sweeping the globe.

We need trade but it can’t last as it is.

Everyone worth knowing agrees that climate change is repainting the world beyond recognition right in front of us. An implication of this is extreme price volatility for crude oil. At time of publishing, Iran is threatening to shut the Hormuz Strait as a result of US and Israeli bombing, which would single-handedly devastate the global oil trade. The term “peak oil” refers to the point at which conventional petroleum production will begin a permanent decline, leading to increases in scarcity and dirtier alternatives such as tar sands. Peak oil has even already come to pass in some countries such as the USA. This is further reflected in trends of people training to transfer from oil industry jobs into renewable industries. However promising this might be to a great energy shift, certain aspects of our economy are heavily if not completely reliant on oil. Juggernaut among these are the massive container ships carrying 1.7 billion tonnes of shipping containers per year (to say nothing of tankers with liquid cargo).

When I say these boats are big, if you haven’t seen them in person, it may be hard to conceptualise. A single small container ship might carry 1,100 shipping containers while the largest in service, such as the MSC Irina, have a capacity of up to 24,300 TEUs (each equivalent to a twenty foot shipping container). It carries up to 240,000 DWTs (Dead Weight Tons) of cargo. This ship is longer than the Auckland Sky Tower is tall. It’s 60 metres wide. It’s a marvel of human audacity that these behemoths even exist, much less that they float. And without them our economies are… well kind of screwed.

Supermassive Emma Maersk container ship.

Around 90% of goods are carried by sea. That’s a staggering figure. And sure, maybe along degrowth lines we don’t actually need a super-ship carrying bobbleheads from Mexico to London, or pineapples from Costa Rica to the Philippines (for canning) and then back to LA to be distributed by diesel jugging 18-wheelers across the continental US. Ideally we could also eliminate the somewhat ironic ship based transport of crude oil in tankers which constitutes nearly 30% of all maritime cargo. Containers on the other hand, carry some 23% of all dry cargo by volume, but account for 70% of the value of all shipped cargo. Bulk dry cargo is often manufacturing precursors like iron ore or coal but can be things like grain as well. Cargo ship goods range from electronics, heavy machinery, food, cars, steel, wood, textiles, humanitarian aid, to even potentially things like vaccines that can’t be easily produced in every individual nation or regionally within a single nation.

But international (and regional) trade isn’t just good, it’s critical to the basic functioning of a cohesive economy. The methods by which globalisation of markets has been enacted in practice are often destructive and colonial beyond measure. This is particularly true of the complex legacies of maritime trade. Acknowledging the risks associated with doing international exchange poorly, an interconnected world makes us all richer, and not just economically. Populist ultranationalism and trade isolationism results in economic destruction. Through connectivity people are able to share not just goods, but also ideas and culture. Though there’s an immeasurable subjective boon to interconnected global populaces, economically alone, in 2019 annual global shipping trade was valued at $24.5 trillion NZD. New Zealand describes itself as a “trade dependent economy” and exported goods valued at nearly $70 billion NZD in 2022 alone.

The oil burning cargo ships and tankers most of this trade happens via are still more energy efficient than rail, air, or road and getting more efficient over time. There are additional regulatory pushes to decrease greenhouse gasses from shipping. However, maritime shipping still accounts for 3% of global carbon emissions per year. Based on current growth patterns, it is expected to be closer to 10% by 2050. A single ship like the Emma Maersk might use the Heavy Oil equivalent of 6,500 tanks of gas in a car per day. This is staggering even if that is to move a proportionately much higher mass of goods than the cars.

In a world facing the terrifying precipice of climate change, this is obviously unsustainable.

Only an evolution in shipping can save us.

So why don’t we just make them all electric, wind, or even slap on a fun-sized nuclear reactor? It turns out, however, that this is one of the stickiest problems of our era.

With regard to cute, little kawaii nukes, though there is work on small nuclear reactor engines for maritime, if you have a uranium hookup you should probably not be talking about it with anyone.

Wind is great. Companies like Sail Cargo in Costa Rica are building sail boats that can move nearly 200 metric tonnes of goods (to say nothing of the elegant Haitian sloop). However, modern ports are tightly scheduled, making the time volatility of wind more complicated to coordinate. There are even cool hybrid ideas in practice such as Sky Sails who offer high-altitude kites above cargo ships, reducing the overall amount of fuel they need to burn.

As for electricity, there are huge economies of scale that benefit the supermassive oil fueled cargo ship. Notably, the momentum they generate as well as their shape and weight, help them to efficiently wave break and travel long distances across the volatile deep sea. That means they are relatively fast, efficient, and reliable. But beyond just this there are other pesky aspects ordained by that old chestnut…. physics.

Critical among these engineering limits is the energy density problem. In short, oil is a highly energy dense (if dirty) energy source. If you add more oil and cylinders you get more power. However with batteries you quickly run into problems. Before you know it, the weight of the batteries you would need has become greater than the mass of the booty you’re trying to shepard across the isle.

Because of this, even though electric engines themselves are said to be quite efficient, large electric vehicles are generally forced to be relatively short distance compared to their oil counterparts. There are already electric planes but they only do short regional trips (for now). Air New Zealand is heading an effort towards electric cargo flights between Wellington and Blenheim. There are already electric ferries and shipping container boats but they are generally only for short trips as well. The electric tugboat named Sparky that operates in Tāmaki Makarau (Auckland) is expected to save 465 tonnes of fuel annually.

There are additionally electric ferries for cars and people, proliferating rapidly across the globe including the Ika Rere, built in Te-Whanganui-a-Tara (Wellington) by WEBBCo and Meridian Energy. Electric ferries like these are often made to be ultra-light in order to focus on speed for the human passengers on-board and compensate for the weight gains and energy density issues of electric batteries. Conversely, shipping can afford to move slower and are generally made of steel which are traditionally compensated for by increases in diesel engine size and fuel capacity.

A representative of the NZ based company EV Maritime wrote to me:

“Batteries are heavy, and less energy dense than diesel, so for us to build fully electric fast passenger ferries, we must prioritise propulsive efficiency and minimising weight in all other aspects of the vessel. We have seen electric vessels around the world fail to hit their reported top speed, and often this is due to mismanaged weight gains, as such, going slow and being fully electric isn’t so difficult to achieve, but our goal is to go fast.”

Existing electric shipping container vessels are often not open sea ships but rather coastal or inland barges. Some, such as the Danish E-Ferry “Ellen” can gently and quietly pass through beautiful canals. Meanwhile in Tasmania the “worlds largest electric boat” is being built to act as a ferry in South America. Electric barges have another advantage over traditional container ships in that they can be RoRo (roll-on, roll-off) like an inter-island car ferry. This is simpler than relying on port authorities to coordinate use of the large cranes. Instead, a long range electric 18-wheeler such as the Windrose E1400 in NZ, can simply rock-up, get the goods, and be gone. There was even a proposal in Tāmaki to place imported cars on electric coastal barges but the company claims the costs to be “eye-watering.”

Despite the straightforwardness of barges, there are efforts to develop electric and hybrid container ships and tankers as well. The first zero-emission all-electric tanker was launched in Japan by Asahi Tanker in 2021. Not only is it carbon-zero, it also achieves zero emissions of NOx, SOx and particulates. All the while being quiet and smooth, no doubt to the delight of port and crew.

In 2021 the “first” fully electric cargo ship, the Yara Birkeland, was completed in Norway boasting an impressive but relatively small, 120 TEUs. Building upon this success, in 2024 the Chinese state owned company COSCO Shipping launched a significantly larger 9,000 tonne, 700 TEU fully electric container ship with over 50,000 kWh in batteries! With the full stock of batteries on board it can travel lengths that would cost more than 13,000 tonnes of fuel in a traditional cargo ship. It currently runs a weekly service between Shanghai and Nanjing along the Yangtze river, more than 3 times the length of the ferry trip across Te-Moana-o-Raukawa (the Cook Strait).

Although these quite large electric vessels are extremely exciting (to nerds), there’s something to be said for their tinier siblings as well. In Singapore, the Hydromover can ferry about 25 tonnes of cargo. Like their electric barge cousins, this raises considerations about the possibilities of swarms of smaller boats more agile for inland shipping where large-mass for wave breaking is less important. Many companies are even turning towards total automation of these systems.

Despite the progress, fully electric deep-sea shipping is still broadly considered to be not yet viable. However regional routes and hybrid solutions are considered to be not just possible but economically viable, controlling for real world economic and material conditions. On an island nation like Aotearoa, or any nation with a decent canal river system, you can imagine people converting something like a landing barge into a full electric craft capable of weaving the precarious thread between smaller towns without major ports. As well, domestic or regional shipping via a feeder size container ship with some deep water capability is completely viable given current technology. More research is needed in order to analyse the Total Available Market for interventions such as these.

A potentially convertible small landing barge that would allow regional resilience in the face of climate change.

While pure electrification is a noble goal, hybrid power systems can integrate with existing “e-methanol” efforts which utilise a carbon neutral process to create a renewable synthetic methanol. Its production process uses captured carbon dioxide (CO2) and “green hydrogen.” The green hydrogen is produced via water electrolysis powered by renewable energy like wind or solar. However, battery-powered vessels are still significantly more energy efficient than those using e-fuels like methanol. Battery systems require up to 65% less renewable energy over their life cycle.

While lithium-ion and hydrogen fuel cells are the most common EV batteries, they both come with serious issues. As a result of this, new contenders such as solid state batteries and the condensed battery by the inspirational CATL, are emerging with increased energy density, life-span, and charging speed. Even more of a boon, they’re less likely to go boom!

In order to truly glimpse a carbon-zero shipping future there are additional needs though. The first and most important is investment, both public and private. It is no coincidence that COSCO Shipping is state-owned. China is heavily investing in green technology and profiting handily from doing so. Similarly, the EU itself was the largest funder of the e-ferry Ellen. However, even juggernaut private companies like Maersk (spot them on seemingly every port or train around the world, look for an oogle hanging nearby) are extremely interested in green shipping, and willing to foot some of the financial risk.

Aside from just investment in the ships themselves though, ports also need substantial upgrades to support high-power charging. CentrePort in Wellington has already made a humble start. As it stands Meridian already supplies the electric Ika Rere ferry with renewably generated power.

Additionally, current battery room designs limit energy density. In the future, swappable and containerised battery units could improve space and distance efficiency. Indeed, Japan is already building a 140 metre mobile battery tanker. In addition to all of these factors, low-carbon electricity isn’t always accessible on major shipping routes, posing a barrier to widespread adoption.

As for Aotearoa, coastal shipping on barges or container ships is viable. Additionally, a fully electric container ship could already sail (so to speak) across Te-Moana-o-Raukawa (the Cook Strait). Though the trip to Australia is not currently realistic for a pure electric solution, even this could be targeted for both hybrid power systems and synthetic “e-methanol” produced domestically using renewable energy sources. Aotearoa already gets most of its electricity renewably, which could be used to power batteries or create e-methanol. Although maybe the baby was thrown out with the bathwater with regard to clean nuclear energy, these other alternatives could expand to provide unlimited energy to a post-oil Aotearoa. This would reduce our precarious foreign energy reliance and boost our domestic economy, all while presenting opportunities for various Iwi to hold sovereign control over clean energy production and trade (Iwi consultation desperately needed here). Aotearoa Circle has partnered with Australian organisations to green the trans-Tasman route using alternative fuels.

Right now in the global economy, there’s a green-tech arms race occurring alongside battles for AI and computing dominance. Both nation-state and private interests are vying for influence in a rapidly expanding marketplace. As carbon regulations catch the up-draft provided by rising and volatile petrol costs, a critical mass of VC investment will continue to converge on a range of solutions to these problems. Electric ferries, barges, container ships, and tankers are sure to be a part of this.

So whether you’re motivated by fear of a climate change hellscape for you and your children, concerned for our responsibility as kaitiaki of the lands and seas, pure capitalist self-interest, or you’re just really invested in getting your foreign knick-knacks, you’ve got skin in the game.